Issue

No.14 - Into New Lands

The

teacher must orient his work not on yesterday's

development in the

child but on tomorrow's.

– Lev

Vygotsky

Contents

The

Stage meets Life

When fiction meets reality

An

Obituary for a Concept

Creatively exploring concepts

At

the Edge of the Event

In the realm of disinterest and distance

Being

a Child

A world once lived

A

Father’s Hands

Living with ability/disability

The

Day Our Son is Due

What happens at shared moments

Who

Owns Matilda?

Other sides to songs

A

Music Maverick

Confronting sound

Taking

Cinema Beyond

Being true to a vision

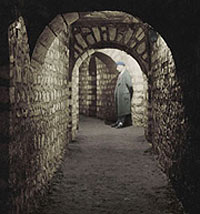

Subterranean

Spaces

A world beneath

In

Search of Southern Lights

The effect of a light show

Bring

on the Media Manipulators

Who is doing what?

When

Old Images Resonate

Using multi-media to create new meanings

An

autumn leaf floating

The beauty in teaching

Welcome

to Edition # 14 of The Creative Teaching Space.

Once

again I pursue an interest in strategies that may open learning possibilities.

I draw ideas

from many sources on the Internet, from my travels, and ideas mentioned

by other people. Some people may call my role as that of a conduit.

Whatever

your response to these strategies continue to explore new possibilities

in teaching and learning. The field is endless. Even the simplest of ideas

may motivate a student on his or her own path of discovery. Artists, writers,

etc, build ideas upon sustained thought. The simplest of ideas may become

a beautiful bridge that takes us to a new land of opportunity!

The

Stage meets Life

I have recently been

reading the lovely poetry of Wislawa Szymborska. This acclaimed winner

of the 1996 Nobel Prize for Literature, who gave an interesting acceptance

speech, writes in Polish and is well translated in a number of editions

of collected work. I have Poems

New and Collected, Harcourt, 1998.

Wislawa Szymborska’s

poetry is often built upon a central concept. Her work would be valuable

for teachers and students who wish to investigate how important concepts

can be explored through prose.

In a number of poems

Wislawa Szymborska writes about a strange connection between theatre and

everyday life. In Theatre Impressions she explores the importance

of the Act Six of a play, where the actors take the curtain call and bow

to the crowd:

The

bows in pairs –

rage extends its arms to meekness,

the victim’s eyes smile at the torturer,

the rebel indulgently walks beside the tyrant.

………………………………………………

Now enter, single file, the hosts who died earlier on,

In Acts 3 and 4, or between scenes.

And here I am reminded

of a similar reference in a song by Laurie

Anderson.

One

Beautiful Evening

It's

like at the end of the play and all the actors come out

And they line up and they look at you.

And horrible things have happened to them during the play

And they stand there while you clap and now what?

What happens next?

What ironies can

we find in the junction where the world of fiction meets reality?

An Obituary for a Concept

Increasingly as teaching

focuses on concepts so we need to remain sensitive to creative ways of

exploring concepts.

Here is an idea that

came to me via a joke email. Take note of how joke emails can be used

in learning!

A concept such as

Common Sense is given an obituary. What other concepts can have an obituary?

Ask students to investigate how obituaries are written. Then ask them

to take a figurative leap. You can even ask students to dissect the values

underpinning each obituary. There are certainly a range of values within

the following piece that deserve dissection.

C.

Sense (Birth date Unknown)

Today

we mourn the passing of a beloved old friend by the name of Common Sense

who had been with us for many years. No one knows for sure how old he

was since his birth records were long ago lost in bureaucratic red tape.

He

will be remembered as having cultivated such value lessons as knowing

when to come in out of the rain, why the early bird gets the worm and

that life isn't always fair. Common Sense lived by simple, sound financial

policies (don't spend more than you earn) and reliable parenting strategies

(adults, not kids, are in charge).

His

health began to rapidly deteriorate when well intentioned but overbearing

regulations were set in place. Reports of a six-year-old boy charged

with sexual harassment for kissing a classmate; teens suspended from

school for using mouthwash after lunch; and a teacher fired for reprimanding

an unruly student, only worsened his condition. It declined even further

when schools were required to get parental consent to administer aspirin

to a student; but could not inform the parents when a student became

pregnant and wanted to have an abortion.

Finally,

Common Sense lost the will to live as the Ten Commandments became contraband;

churches became businesses; and criminals received better treatment

than their victims. Common Sense finally gave up the ghost after a woman

failed to realize that a steaming cup of coffee was hot, she spilled

a bit in her lap, and was awarded a huge settlement.

Common

Sense was preceded in death by his parents, Truth and Trust, his wife,

Discretion; his daughter, Responsibility; and his son, Reason.

He is survived by two stepbrothers; My Rights and Ima Whiner. Not many

attended his funeral because so few realized he was gone.

If

you still know him pass this on, if not join the majority and do nothing.

At the Edge of the Event

I recently saw the

documentary Meeting People is Easy: A Film by Grant Gee about Radiohead. Radiohead being

the English rock group.

As I was viewing Meeting People is Easy I came across a fascinating scene. Radiohead

are seen performing their hit song Creep live on stage. Instead

of seeing a close up of the band the camera is positioned well outside

the space of the stage. It is in the foyer. We see the band silhouetted

in the distance and we see people coming and going. Some are perhaps going

to the toilet; some may be talking to friends. What is fascinating is

the director’s choice to film the performance from a distance.

How often do we see

close up band performances and over-excited crowds? The above scene is

quite distant and matter of fact. It brought to my attention the idea

of being at the edge of an event. There is always that edge of

the event: the policeman standing in the wings, the bored audience member

or the technician with other priorities.

What happens if we

take that step back from an event, to its edges? What do we find? What

does this tell us about the event, how we focus on events, and on the

diversity of people? We know that Tom Stoppard fore-grounded the two minor

characters from Hamlet, Rosencrantz and Guildernstern, in his play Rosencrantz

and Guildernstern are Dead.

How could we open

learning possibilities by changing focus?

Being a Child

The following song

on the tail end of the album The Philosopher’s Stone, by Van Morrison,

an album of out-takes, is an evocative spoken word tribute to childhood.

Written by Peter

Handke and sung/spoken by, it contains many views of childhood.

Students may wish

to explore how the experience of being a child is different from their

current experience. What changes? Why? Can these changes be explored creatively

in e.g. a similar poem/song?

Song

of Being a Child

When

the child was a child….

It

walked with arms hanging

Wanted the stream to be a river and the river a torrent

And this puddle, the sea

When the child was a child, it didn't know

It was a child

Everything for it was filled with life and all life was one

Saw the horizon without trying to reach it

Couldn't rush itself

And think on command

Was often terribly bored

And couldn't wait

Passed up greeting the moments

And prayed only with its lips

When the child was a child

It didn't have an opinion about a thing

Had no habits

Often sat crossed-legged, took off running

Had a cow lick in its hair

And didn't put on a face when photographed

When

the child was a child

It was the time of the following questions

Why am I me and why not you?

Why am I here and why not there?

Why did time begin and where does space end?

Isn't what I see and hear and smell

Just the appearance of the world in front of the world?

Isn't life under the sun just a dream?

Does evil actually exist in people?

Who really are evil?

Why can't it be that I who am

Wasn't before I was

And that sometime I, the I, I am

No longer will be the I, I am?

When

the child was a child

It gagged on spinach, on peas, on rice pudding

And on steamed cauliflower

And now eats all of it and not just because it has to

When the child was a child

It woke up once in a strange bed

And now time and time again

Many people seem beautiful to it

And now not so many and now only if it's lucky

It had a precise picture of paradise

And now can only vaguely conceive of it at best

It couldn't imagine nothingness

And today shudders in the face of it

Go for the ball

Which today rolls between its legs

With its I'm here it came

Into the house which now is empty

When

the child was a child

It played with enthusiasm

And now only with such former concentration

Where its work is concerned

When the game, task, activity, subject happens to be its work

When

the child was a child

It was enough to live on apples and bread

And it's still that way

When the child was a child berries fell

Only like berries into its hand

And still do

The fresh walnuts made its tongue raw

And still do

Atop each mountain it craved

Yet a higher mountain

And in each city it craved

Yet a bigger city

And still does

Reach for the cherries in the treetop

As elated as it still is today

Was shy in front of strangers

And still is

It waited for the first snow

And still waits that way

When the child was a child

It waited restlessly each day for the return of the loved one

And still waits that way

When the child was a child

It hurled a stick like a lance into a tree

And it's still quivering there today

The

child, the child was a child

Was a child, was a child, was a child, was a child

Child, child, child

When the child, when the child, when the child

When the child, when the child

The child, child, child, child, child

And

on and on and on and on and onward

With a sense of wonder. Upon the highest hill

Upon the highest hill

When the child was a child

Are you there

Shassas, shassas

Up on a highest hill

When the child was a child, was a child, was a child

Was a child, was a child, was a child (Fade to end)

A Father’s Hands

The following story My Father’s Hands by Calvin R. Worthington, is an evocative story

detailing one man’s experience of illiteracy. Moving, and tragic, it shows

the impact that reading – or its lack – has on a person’s life.

Students may like

to use this story as a starting point to discuss how we learn in life.

What impact does a disability have on a person? How do people overcome

these disabilities?

My

Father’s Hands

Calvin

R. Worthington

His

hands were rough and exceedingly strong. He could gently prune a fruit

tree or firmly wrestle an ornery mule into harness. He could draw and

saw a square with quick accuracy. He had been known to peel his knuckles

upside a tough jaw. But what I remember most is the special warmth from

those hands soaking through my shirt as he would take me by the shoulder

and, hunkering down beside my ear, point out the glittering swoop of

a blue hawk, or a rabbit asleep in its lair. They were good hands that

served him well and failed him in only one thing: they never learned

to write.

My

father was illiterate. The number of illiterates in our country has

steadily declined, but if there were only one I would be saddened, remembering

my father and the pain he endured because his hands never learned to

write. He started first grade, where the remedy for a wrong answer was

ten ruler strokes across a stretched palm. For some reason, shapes,

figures, and recitations just didn’t fall into the right pattern inside

his six-year-old towhead. Maybe he suffered from some type of learning

handicap such as dyslexia. His father took him out of school after several

months and set him to a man’s job on the farm.

Years

later, his wife, with her fourth-grade education, would try to teach

him to read. And still later I would grasp his big fist between my small

hands and awkwardly help him trace the letters of his name. He submitted

to the ordeal, but soon grew restless. Flexing his fingers and kneading

his palms, he would declare that he had had enough and depart for a

long, solitary walk.

Finally,

one night when he thought no one saw, he slipped away with his son’s

second-grade reader and labored over the words, until they became too

difficult. He pressed his forehead into the pages and wept. "Jesus—Jesus—not

even a child’s book?" Thereafter, no amount of persuading could

bring him to sit with pen and paper.

From

the farm to road building and later factory work, his hands served him

well. His mind was keen, his will to work unsurpassed. During World

War II, he was a pipefitter in a shipyard and installed the complicated

guts of mighty fighting ships. His enthusiasm and efficiency brought

an offer to become line boss—until he was handed the qualification test.

His fingers could trace a path across the blueprints while his mind

imagined the pipes lacing through the heart of the ship. He could recall

every twist and turn of the pipes. But he couldn’t read or write.

After

the shipyard closed, he went to the cotton mill, where he labored at

night, and stole from his sleeping hours the time required to run the

farm. When the mill shut down, he went out each morning looking for

work—only to return night after night and say to Mother as she fixed

his dinner, "They just don’t want anybody who can’t take their

tests."

It

had always been hard for him to stand before a man and make an "X"

mark for his name, but the hardest moment of all was he placed "his

mark" by the name someone else had written for him, and saw another

man walk away with the deed to his beloved farm. When it was over, he

stood before the window and slowly turned the pen he still held in his

hands—gazing, unseeing, down the mountainside. I went to the springhouse

that afternoon and wept for a long while.

Eventually,

he found another cotton-mill job, and we moved into a millhouse village

with a hundred look-alike houses. He never quite adjusted to town life.

The blue of his eyes faded; the skin across his cheekbones became a

little slack. But his hands kept their strength, and their warmth still

soaked through when he would sit me on his lap and ask me to read to

him from the Bible. He took great pride in my reading and would listen

for hours as I struggled through the awkward phrases.

Once

he had heard "a radio preacher" relate that the Bible said,

"The man that doesn’t provide for his family is worse than a thief

and an infidel and will never enter the kingdom of Heaven." Often

he would ask me to read that part to him, but I was never able to find

it. Other times, he would sit at the kitchen table leafing through the

pages as though by a miracle he might be able to turn to the right page.

Then he would sit staring at the Book, and I knew he was wondering if

God was going to refuse him entry into heaven because his hands couldn’t

write.

When

Mother left once for a weekend to visit her sister, Dad went to the

store and returned with food for dinner while I was busy building my

latest homemade wagon. After the meal he said he had a surprise for

dessert, and went out to the kitchen, where I could hear him opening

a can. Then everything was quiet. I went to the doorway and saw him

standing before the sink with an open can in his hands. "The picture

looked just like pears," he mumbled. He walked out and sat on the

back steps, and I knew he had been embarrassed before his son. The can

read "Whole White Potatoes," but the picture on the label

did look a great deal like pears.

I

went and sat beside him, and asked if he would point out the stars.

He knew where the Big Dipper and all the other stars were located, and

we talked about how they got there in the first place. He kept that

can on a shelf in the woodshed for a long while, and a few times I saw

him turning it in his hands as if the touch of the words would teach

his hands to write.

Years

later, when Mom died, I tried to get him to come live with my family,

but he insisted on staying in his small frame house on the edge of town

with a few farm animals and a garden plot. His health was failing, and

he was in and out of the hospital with several mild heart attacks. Old

Doc Green saw him weekly and gave him medications, including nitroglycerin

tablets to put under his tongue should he feel an attack coming on.

My

last fond memory of Dad was watching as he walked across the brow of

a hillside meadow, with those big, warm hands—now gnarled with age—resting

on the shoulders of my two children. He stopped to point out, confidentially,

a pond where he and I had swum and fished years before. That night,

my family and I flew to a new job and new home, overseas. Three weeks

later, he was dead of a heart attack.

I

returned alone for the funeral. Doc Green told me how sorry he was.

In fact, he was bothered a bit, because he had written Dad a new nitroglycerin

prescription, and the druggist had filled it. Yet the bottle of pills

had not been found on Dad’s person. Doc Green felt that a pill might

have kept him alive long enough to summon help.

An

hour before the chapel service, I found myself standing near the edge

of Dad’s garden, where a neighbor had found him. In grief, I stopped

to trace my fingers in the earth where a great man had reached the end

of his life. My hand came to rest on a half-buried brick, which I aimlessly

lifted and tossed aside, before noticing underneath it the twisted and

battered, yet unbroken, soft plastic bottle that had been beaten into

the soft earth.

As

I held the bottle of nitroglycerin pills, the scene of Dad struggling

to remove the cap and in desperation trying to break the bottle with

the brick flashed painfully before my eyes. With deep anguish I knew

why those big warm hands had lost in their struggle with death. For

there, imprinted on the bottle cap, were the words, "Child-Proof

Cap—Push Down and Twist to Unlock." The druggist later confirmed

that he had just started using the new safety bottle.

I

knew it was not a purely rational act, but I went right downtown and

bought a leather-bound pocket dictionary and a gold pen set. I bade

Dad good-bye by placing them in those big old hands, once so warm, which

had lived so well, but had never learned to write.

Another story of

the same name, by Paul

M. Clements, details a father’s life told through the character of

his hands. Can students write similar biographies by choosing a particular

focus e.g. hands, a face, arms?

The Day Our Son is Due

The poem, Redknots,

emphasises that important moments can be linked to other significant events.

Imagine a scene.

What other events are happening in the world? What connections can be

made between events? Do these events connect? Do they need to connect?

Encourage students

to explore how we can connect phenomena and in doing so create new types

of meaning.

Who Owns Matilda?

In Australia our

most significant song is probably Waltzing Matilda. It would certainly

be the most internationally recognized Australian song. Yet how many people

know its history and the fact that when it was played at the Sydney Olympics

the payment for its use went to an American copyright holder?

The following site,

set up by Roger Clarke, Copyright

in 'Waltzing Matilda', explores the story of this song.

Songs have their

own history, their own cultural value, and their economic value e.g. legal

rights. The song Waltzing Matilda, as does Happy

Birthday, reveals that songs are much more than words.

Consider the possibility

of exploring a song from a transdisciplinary perspective – investigating

it e.g. economically/mathematically, culturally, historically, musically,

etc.

Explore how teachers

can work together to reveal how a range of disciplinary approaches surround

even the simplest of songs. This could be a wonderful chance to explore

the breadth of the music industry. Students may even like to choose a

song and capture its essence, through research, or imaginative interpretation.

A Music Maverick

The American composer Harry

Partch was well ahead of his time when he designed and created musical

landscapes, often with his own created instruments, well before this became

fashionable in the 1960s or currently within our digital era.

Partch’s work is

very eccentric. One even has the opportunity of digitally playing his

instruments at this

site.

Whenever we see or

play odd instruments at e.g. music festivals, one should be reminded of

people like Partch who chose to confront the rules of music. What are

these rules? Can they be broken? Were there other people like Partch in

other cultures? Didn’t every first instrument builder have to confront

a tradition? What is currently happening in music that can be confronting?

Perhaps students

can create their own soundscapes, including their own instruments.

Every sense has its

own tradition. Sound is not a fixed entity. We all hear slightly differently.

Sound has changed through the ages and is currently changing. Encourage

students to investigate the culture of sound by starting with people like Harry

Partch.

Taking Cinema Beyond

The great Taiwanese

filmmaker Hou

Hsiao-hsien is quoted in the following article: In

Search of New Genres and Directions for Asian Cinema.

It is a beautiful

quote that challenges the often static perception of cinema – one created

by some funding bodies and popular culture.

Films, like any art

form, can encourage the uniqueness of the individual.

Hou Hsiao-hsien knows

this and the beauty of his vision is revealed in his films.

We may need to remind

ourselves of such quotes/visions in a world that too often pushes a sameness.

You

have to find the right way to approach the right subject for yourself.

No one can do that for you. You may not be aware of your great potentiality.

You do not need to make films that we think are proper, or feel compelled

to make certain kinds of films because they have been praised or recognised.

Never let yourself be tied up by these thoughts. Be creative and unpredictable

for every film you make. That’s best. This is all I want to say.

And sometimes that

is all that is needed to be said!

Subterranean Spaces

I can remember that

when I lived in Ballarat, in Victoria, there was sometimes the sense of

a subterranean world. Ballarat had been a large gold mining town in the

middle of the nineteenth century and it was littered with mine shafts.

Besides its mining

shafts Ballarat also seemed to contain many vaults. After all, the gold

had to be stored somewhere. Many buildings had basements or vaults. There

was even a story that a local pub had a shaft, created by miners, used

to evade mining tax collectors, in the mid 1800s.

All cities have their

vaults, their basements, and their utility structures such as pipes, channels

or even subways. The following sites allow us to investigate the subterranean

world of Paris, and U.K. cities.

Ask students to investigate

the world beneath their city or town. Perspectives can be as varied as

those of town planning to imagined traditions – the sewer in the horror/war

movie.

What is evoked by

the ‘underground’? How is it experienced by people? Imagine speaking to

a miner, a railway maintenance worker, or a creative writer about the

experience of being under a city.

In Search of Southern Lights

It took three years

for me to see the Southern Aurora, or the Southern Lights, above Hobart.

On a perfect night with just the right amount of mist in the air I was

treated to a dazzling light show across Mt Wellington. This included a

shimmering effect of blue and green light, and rays of green light shooting

across the sky. It was very beautiful and mesmerizing. It made me think

about its beauty as well as its scientific

basis.

What effect do such

events have on people? How are such events viewed today? How were they

viewed in the past? Auroras, like lightning storms, can be surrealistic as revealed in photos.

Here we may have

a lovely opportunity for students to combine scientific fact – meteorological

truth – with artistic viewpoints. How could an artist experience an

aurora? How could one be experienced by a meteorologist? What is shared?

What is different?

Bring on the Media Manipulators

Bring on the media

manipulators. Let’s highlight who is doing what with images and for what

effect!

The following

site shows what media outlets do to change images. Photographs have

been manipulated for years. Now, though, it is even easier with digital

technology.

When Old Images Resonate

Old photographs can

have a strange resonance. The work of Ross

Gibson and Kate Richards in the CD-Rom Life

After Wartime uses old police crime photographs, music, and the

random building of images, to create a disturbing sense of place. Yes,

these were crime scenes, something happened, yet we are never quite sure

– many of the initials police records identifying the scene and location

are now missing. As a result the exercise takes on a poetic quality.

A recent exhibition

by Ross at ACMI in Melbourne – Street

X-Rays – uses photographs of old crime scenes and juxtaposes them

with video footage of those scenes in the present day. This is very interesting.

The current places take on an ambience – these places look very innocent

in their real time, yet carry their own history.

Images and locations

resonate with meaning. How can we use technology to highlight this power?

Ross Gibson’s work, like many other media artists, show us how new meanings

can be created by the interaction of media technology. How might students

address old images, or locations, through the use of multimedia?

The website Time

Tales is dedicated to found images, those dislocated from their original

owners, yet ones that still carry a certain resonance.

Does, as quoted on

this site "a picture need memories to be an image?"

What is a dislocated

picture without its story or history?

An autumn leaf floating

The following article

entitled Perfect

Day: A Meditation About Teaching (PDF

document) is a good point at which to end this edition of The

Creative Teaching Space.

It is a beautiful

story about teaching. Written by an American teacher Gilbert Valadez

it records the point where personal experience and professional role meet

in the classroom; in this case a time when a grieving teacher finds solace

in the creativity and honesty of children, and is moved in unexpected

ways.

What this story reminds

us is that the best teaching has a naturally spiritual element – not an

imposed spirituality. The best teachers invest their classrooms with a

soulfulness that is as rich and rewarding for themselves, as it is

their students.

Learning is deeply

human. At times there will be strength, at other times vulnerability.

The best teachers are strong but are also able to show their vulnerability.

The measure of a healthy teaching environment is one where the teacher

cares, and the teacher is cared for.

Learning is about

being moved. If we don’t allow the opportunity for ourselves, as teachers,

to be moved, then we are denying the very essence of what makes teaching

a communicative and two-way act.

Darron

Davies

© Copyright In Clued - Ed 2009